|

21 August 1949

21 PERSONS DIED IN A PLANE CRASH INCLUDING THREE RADIO OPERATORS

A Canso R.C.A.F. military aircraft crashed and burned

in Manitoba on 21 August 1949 killing everyone onboard. Amongst the 21 victims

were three radio operators, all married men returning to their families, who had

spent two or more years in the Arctic, at Clyde River

on Baffin Island. The three radio operators were: Radio Operator Addison Bruce Neill of Glencoe, Ont. Radio Operator Cecil Dawn McKenzie of Dartmouth, N.S. Radio Operator B.S. McManus of Halifax, NS

Scroll down this page for details and news of the tragedy

A swath 600 feet long and 60 feet wide was cut through the timber by the Canso aircraft which crashed Sunday night. Bodies and wreckage were strewn over the path cut by the aircraft.

Lying at the end of the 600-foot swath the doomed plane cut through the trees is the largest single remaining piece of the R.C.A.F. amphibious Canso aircraft that plunged into the ground and claimed 21 lives, 80 miles east of Norway House Sunday night (August 21, 1949). Probe into the cause of the crash began Wednesday morning (August 24, 1949) when three investigating R.C.A.F. officers arrived in Winnipeg. In the foreground can be seen one of the trees charred by fire which broke out in the plane when it crashed.

Photo of the crew taken in Churchill, Manitoba a few hours before the crash

A Canso amphibious aircraft similar to the one which crashed

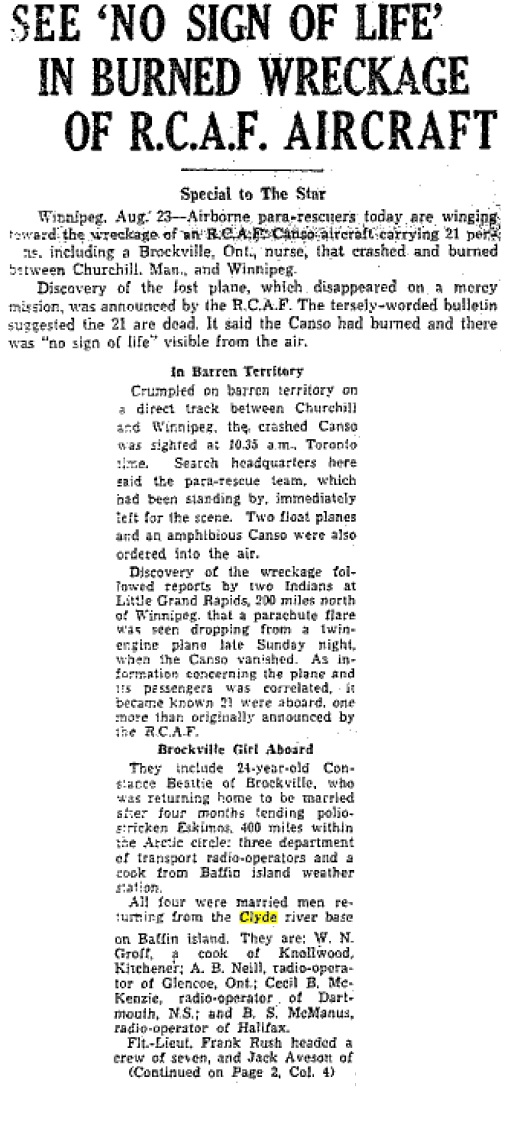

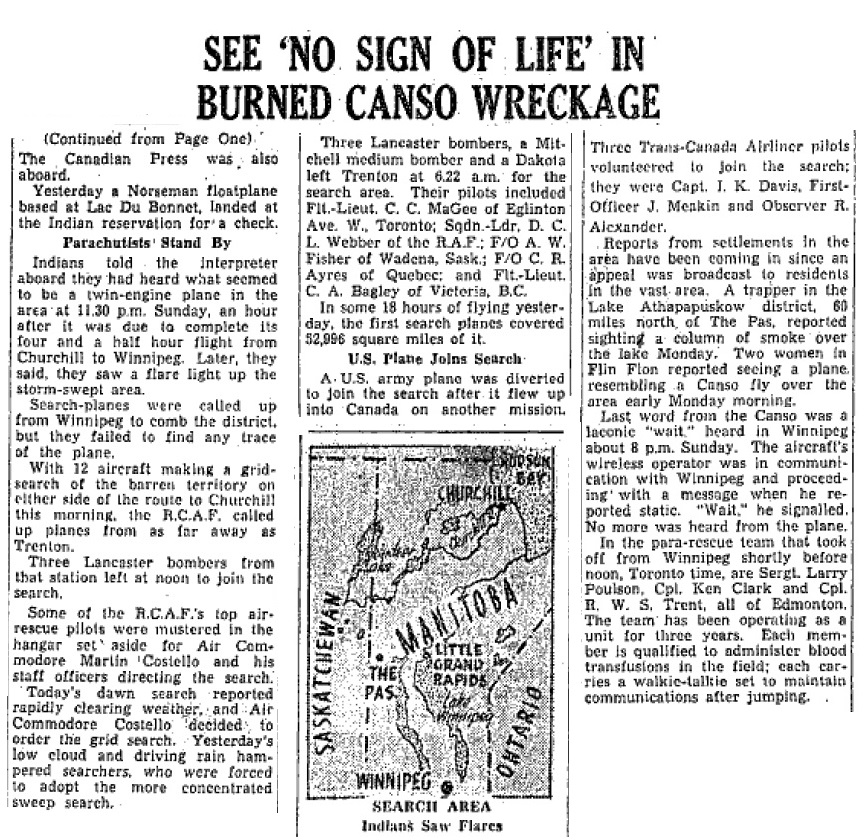

21 KILLED IN R.C.A.F. CANSO CRASH BURNED WRECK FOUND IN NORTHERN MANITOBA AREA LAND PARTY REACHES SCENE OF TRAGEDY Lethbridge Herald Alberta

Winnipeg, Aug. 23 -- The R.C.A.F. disclosed today that all 21 persons aboard an amphibious Canso had been killed in the crash of the plane in northern Manitoba.

he crashed Canso made its routine stops at Clyde River and Chesterfield Inlet without incident. It set out Sunday on the 4 1/2 hour flight to Winnipeg, and the last radio word from it was received around 8 p.m. The R.C.A.F. said Flt. Lt. Avent still was circling the scene of the crash. One of the Cansos en route piloted by Flt. Lt. A. B. Johnston of Simcoe, Ont., of No. 413 Squadron, Ottawa.

Ottawa, Aug. 23. -- (CP) -- The R.C.A.F. today released the names of three more persons missing in an air force Canso aircraft on a flight from Churchill, Man., to Winnipeg. All are members of the transport department. They are CECIL D. McKENZIE, a radio operator of Dartmouth, N.S.; B.S. McMANUS, radio operator of Halifax; W. N. GROFF, a cook from Kitchener, Ont.

Additional names of casualties: 57 Years Of Silence Now-60-year-old documents shed light on the 'racist' aftermath of a plane crash that killed 20 whites and Inuit By Catherine Mitchell Winnipeg Free Press 26 July 2009

Annie Ollie has heard enough.

Searching for years now for some basic truths about a plane crash in Northern Manitoba that took the life of her father's young, polio-stricken sister in 1949, the Arviat resident is struck silent by new facts revealed about the RCAF accident.

The plane crash was this province's greatest air disaster. The RCAF investigation into the cause of the crash was never made public, the truth carefully, purposely hidden for 60 years now.

This spring, spurred on by a call for help from Inuit families in the Eastern Arctic, I went looking for answers to a lot of outstanding questions about the tragedy. A month ago, the government files I requested from Library and Archives Canada arrived. I spent about eight hours combing through the faded copies of microfilmed documents. The details of the investigation's findings are unsettling for Ollie and other residents in Nunavut who lost loved ones when the amphibious plane crashed in a severe storm Aug. 21 1949, near Norway House.

Only three years ago they found out their loved ones were buried in a mass, unmarked grave at the reserve, ending 57 years of mystery surrounding the crash there. Now, they've been given the answer -- or likely the closest thing to it -- to the mystery behind that decision, some explanation for why the bodies of the seven Inuit were treated differently than the 13 others, all white, all from Southern Canada, and taken with care and respect south to Winnipeg, then transported across the country to the hometowns for burial.

That decision to bury the Inuit -- bundled in canvas, placed into a single wooden coffin at the local cemetery -- appears to have been that of a single man, Dr. Joseph P. Moody, who was hired by the federal government to serve at Chesterfield Inlet. Moody handled, by himself, at least in the early days, a virulent polio epidemic that raced through the families and hamlets along the Hudson Bay coast in the winter of 1948 and into 1949.

An RCMP report and memos attached to it indicate that Dr. Moody issued the order not to bring the bodies of the seven Inuit, airlifted out for medical care at Winnipeg's King George Hospital, back to the Arctic. It's a hard landing for the families who have been struggling to understand why the bodies weren't flown home.

"They were so racist," says Annie Ollie, of the mindset of non-aboriginals in authority in the mid-century administration of the Eastern Arctic, a land of nomadic Inuit only just starting to settle into centres with basic, government services.

"My people had to live that (racist attitude). I think it also affected how Dr. Moody made his decisions," says the soft-spoken Ollie. The polio epidemic of 1949 struck with a virulence never before recorded by medical authorities, decimating families and hamlets.

The RCAF Canso was sent to the High Arctic that August to drop off new employees at a Baffin Island weather station, and pick up four weathermen who had been there for two years or more. On the way south, it stopped at Chesterfield Inlet, picking up six polio-stricken Inuit, including Ollie's aunt, 15-year-old Ubluriak, and a Toronto physiotherapist who had answered a call for help from the Health Department that spring. At Churchill, it loaded a Canadian Press reporter and another polio victim, known as Oohotok, 26 of Kazan River. Pilot Francis John Rush, of Winnipeg, took to the air again late in the afternoon.

Hours later, he flew into a violent storm no one had forecast. Coming low over bog country near Big Stone Lake, the pilot cleared a small lake and a rocky outcrop of land on the other side, then smashed into the trees of the bush and crash-landed. All were killed instantly, some with body parts severed. It took days to find the plane and recover the bodies.

The crash caused heartbreak across Canada, to all three coasts. The tragedy, however, was compounded by a monumental betrayal out of the high offices of the Defence Department that hid from Canadians the truth behind, and the government's own culpability in, the crash. In fact, the details were even withheld from the Manitoba attorney general, who deferred calling a routine inquest, assuring the public that the Air Force investigation would reveal all.

"Transcripts of evidence may be released to the Attorney General but the findings and recommendations must not, repeat must not, be disclosed," wrote R.V. Mulligan from Air Force headquarters in Ottawa, on Sept. 10, 1949.

"It's so overwhelming," says Ollie.

Many elderly Inuit remember Dr. Moody, who served at a Chesterfield Inlet hospital run by Catholic missionary nurses.One Rankin Inlet resident, who lost his mother and three other relatives in the crash, is dumbfounded to learn, after all these years, that Moody is the reason the bodies did not come home.

Agnes Adams says her elderly uncle, Francois Kaput, is adamant that Moody never told his family their mother, Arnaluktituaq, her granddaughter, son-in-law and niece would not come back to Chesterfield.

"They were never told the bodies were going to be buried down south," says Adams, whose sister Aniasie (Arnaluktituaq's granddaughter) perished in the crash. "They waited for the bodies (to be sent back) but they never came." It is a cruel blow to her uncles, Kaput and Tony Amarok, who wondered for years where their mother's body lay.

Why the secrecy? Well, for a number of reasons.

The details show that Ottawa's own inadequate weather-forecasting coverage on that route contributed to the tragedy. There were only two federal weather stations relaying forecasts, every three hours, to Churchill. Another pilot who testified said the Air Force crews learned not to rely on the forecasting.

Pilot Rush was told to expect a moderate storm. Instead, the Canso hit a severe thunderstorm with sheet rain and lightning, flying in near-total darkness. This was confirmed by a bush pilot for Lamb Air who flew through the area shortly before the Canso.

The Defence Department summarily rejected the recommendation by chief investigator F. R. West to staff the weather stations along the flight path so hourly reports could be made. The reply was that so few flights were made along the path, the cost was not justified. That was wrong, even in a cold financial calculation, as was pointed out by West, to his credit, who said it was small expense compared to the "loss of one aircraft, to say nothing of its occupants."

Further, the Air Force's court of inquiry found the drop in air pressure the plane encountered caused its altimeter to "over-read by 300 to 600 feet." None of the altimeter information was ever released publicly, nor the fact that the inquiry decided that the error in judgment "of the pilot who proceeded in low height in adverse weather" was to blame. West decided that was it was not in the public interest and "would only embarrass all next of kin."

It was a perverse logic, adopted, I suspect, to avoid public scrutiny of some bad, bureaucratic decisions. Those in charge comforted their consciences by noting that all pilots knew the altimeter readings had to be recalculated to account for atmospheric-pressure changes. Imagine the odds of accurately plotting location while dodging lightning in sheet rain and near-zero visibility and adjusting elevation with an unreliable altimeter. Clearly, it defeated the Canso's seven-man RCAF crew.

There is no comfort in any of this for the families of those who died. For the Inuit, the story unveiled by the faded documents and memos, copied to microfilm and filed away for antiquity, is particularly awful. An RCMP report of the details on how the bodies were handled gives abundant detail about the white bodies and their personal effects, right down to the concern over finding a diamond engagement ring the physiotherapist's fiancÚ had sent to her at Chesterfield Inlet.

An RCMP memo indicates someone recognized the insensitivity of Dr. Moody's order to take the Inuit bodies to Norway House. Underscoring a paragraph that relayed Moody's instructions, a handwritten note to the director of the Northwest Territories and Yukon Administration said: "Apparently Dr. Moody has advised the next of kin of the Eskimos killed in the crash. I think it would be interesting to have a report from him regarding the reaction and his views."

The paper trail stopped there.

For Ollie, having searched for years for the story of the fate of her aunt, the story confirms what she's been told by elders of life with the white man in the days the North was being "settled."

Ollie has been to the mass grave at Norway House.

The story's not over yet. Ollie wants to reclaim the remains of her fathers' sister.

"That day will come that my aunt will be buried where she is from."

|

|

Links - Liens

|